Anchoring Oneself in Purity Through the Discipline of Daily Practice

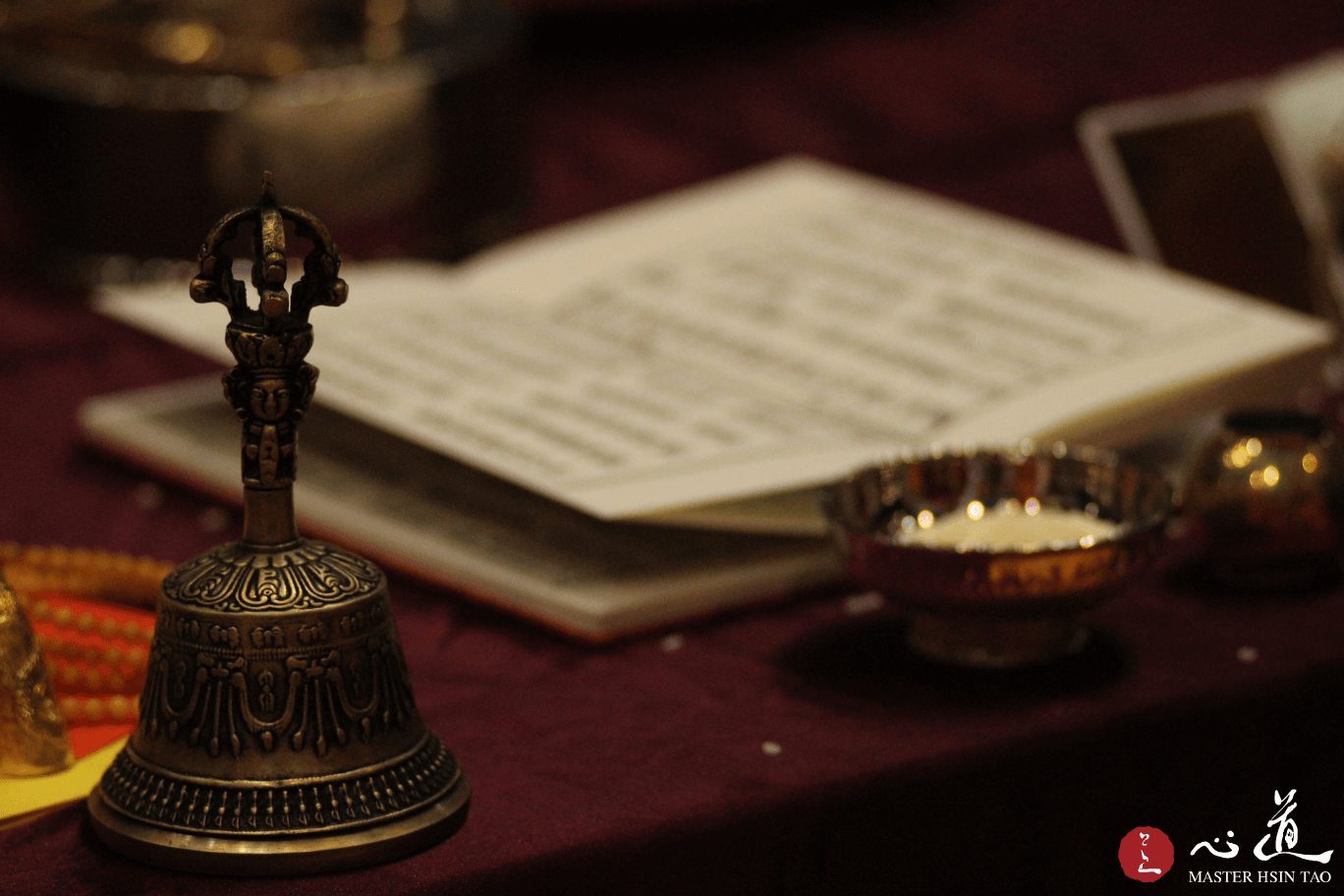

As Buddhist disciples, even when our lives are exceedingly busy and demanding, we must maintain a daily practice routine. Without such practice, we do not know how to tame our own minds; without it, we gain no experiential insight and remain beings who merely get caught up in deluded conceptions. In daily life, if we move through each day in a state of mindlessness—unaware of what we are doing—our thoughts revolve only around self and others, right and wrong, good and bad, gain and loss. We lack any understanding of how to purify our minds, and we end up dwelling in a state that is neither monastic nor lay, thereby becoming incapable of benefiting others. Thus it is imperative to cultivate the routine of doing daily practice, Chan practice, and scriptural recitation. These constitute contemplative practice, which enhances insight and discernment throughout our lives.

As Buddhist disciples, even when our lives are exceedingly busy and demanding, we must maintain a daily practice routine. Without such practice, we do not know how to tame our own minds; without it, we gain no experiential insight and remain beings who merely get caught up in deluded conceptions. In daily life, if we move through each day in a state of mindlessness—unaware of what we are doing—our thoughts revolve only around self and others, right and wrong, good and bad, gain and loss. We lack any understanding of how to purify our minds, and we end up dwelling in a state that is neither monastic nor lay, thereby becoming incapable of benefiting others. Thus it is imperative to cultivate the routine of doing daily practice, Chan practice, and scriptural recitation. These constitute contemplative practice, which enhances insight and discernment throughout our lives.

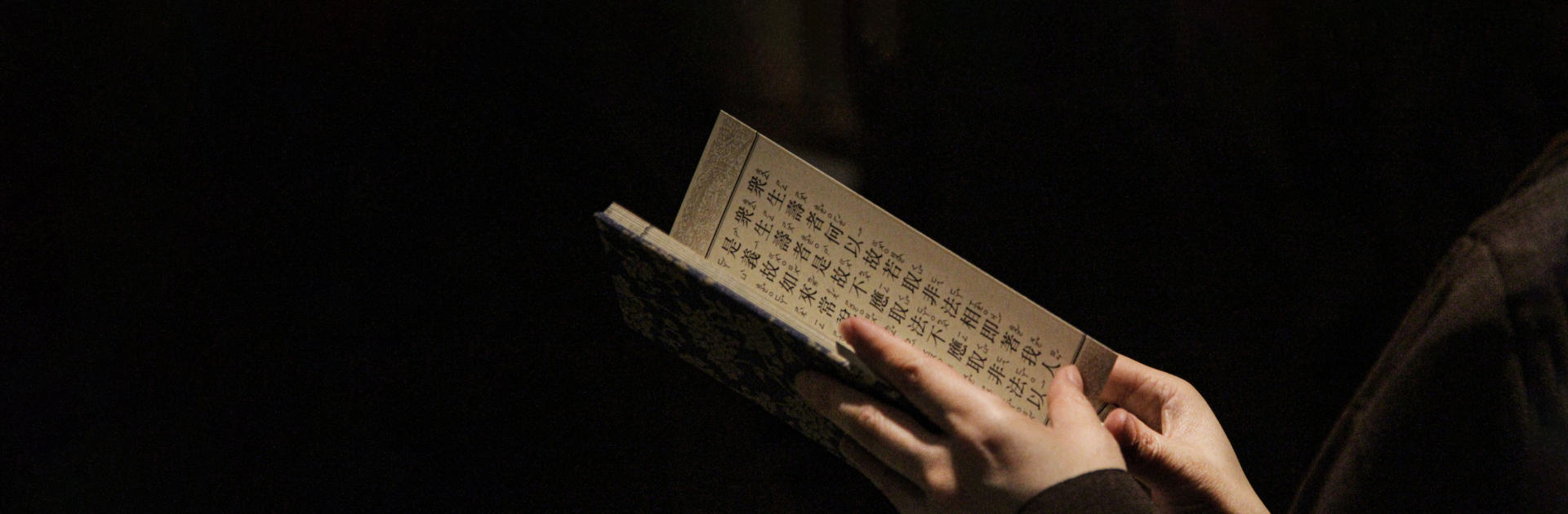

From the age of fifteen onward, I have been reciting the Heart Sutra, the Great Compassion Mantra, as well as the Four Books and Five Classics every day, following the principle of “examining oneself thrice daily.” Each day, I reflect carefully on what I have done wrong and frequently scrutinize my intentions and mental states. To examine one’s mind means to reflect on whether one has wronged others, spoken harshly, committed non-virtuous actions in daily life, or conversely, whether one has helped others and cultivated loving-kindness.

Daily practice is like a rope that binds the mind of an ordinary being, enclosing it within a disciplined boundary so that the mind can rest in integrity and ease. If we do not engage in such practice, our ordinary, habit-bound mind will arise according to conditions and react impulsively to situations. We fail to recognize the nature of a pure state of mind; when ignorance arises, we do not know how to counteract it; when afflictions arise, we do not know how to resolve them. Still less do we know where our aspiration lies. Living in such a vague and muddled way only adds further karmic obscurations.

Daily practice is like a rope that binds the mind of an ordinary being, enclosing it within a disciplined boundary so that the mind can rest in integrity and ease. If we do not engage in such practice, our ordinary, habit-bound mind will arise according to conditions and react impulsively to situations. We fail to recognize the nature of a pure state of mind; when ignorance arises, we do not know how to counteract it; when afflictions arise, we do not know how to resolve them. Still less do we know where our aspiration lies. Living in such a vague and muddled way only adds further karmic obscurations.

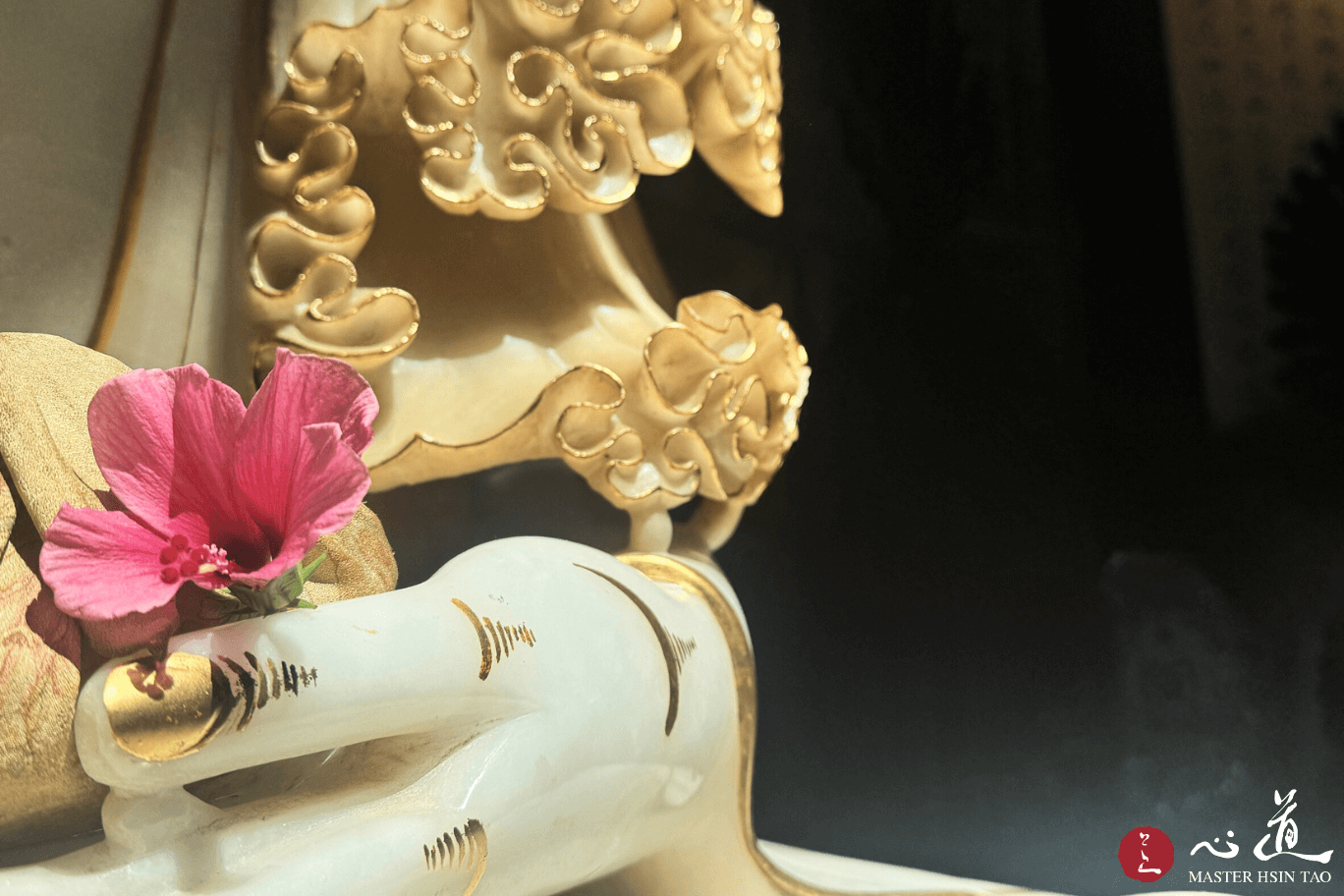

Therefore, we must recognize that indulgence in pleasure marks a regression on the path of Dharma practice, and that indolence and lack of diligence constitute a descent. Continuous diligence gives our lives vitality, principles, and direction—it is a path of unwavering practice. Life is impermanent, and a human lifetime passes swiftly. We must not squander it. To live as a diligent practitioner of the Dharma, benefiting beings widely, is what gives life true value; it is also the most meaningful offering we can make to Buddha Shakyamuni.