Realizing Buddhahood through Notionlessness

In daily life, we must approach all acts of service and dedication with minds imbued with loving-kindness, compassion, joy, and equanimity. The Dharma teaches us to relinquish our selfish intention so that we may fulfill the aspirational power to establish the buddhafield, as well as the aspirational power of generating bodhicitta. Only with such aspirations can we truly engage in meaningful service. Fundamentally, when facing sentient beings, we must be compassionate, patient, and gentle.

In daily life, we must approach all acts of service and dedication with minds imbued with loving-kindness, compassion, joy, and equanimity. The Dharma teaches us to relinquish our selfish intention so that we may fulfill the aspirational power to establish the buddhafield, as well as the aspirational power of generating bodhicitta. Only with such aspirations can we truly engage in meaningful service. Fundamentally, when facing sentient beings, we must be compassionate, patient, and gentle.

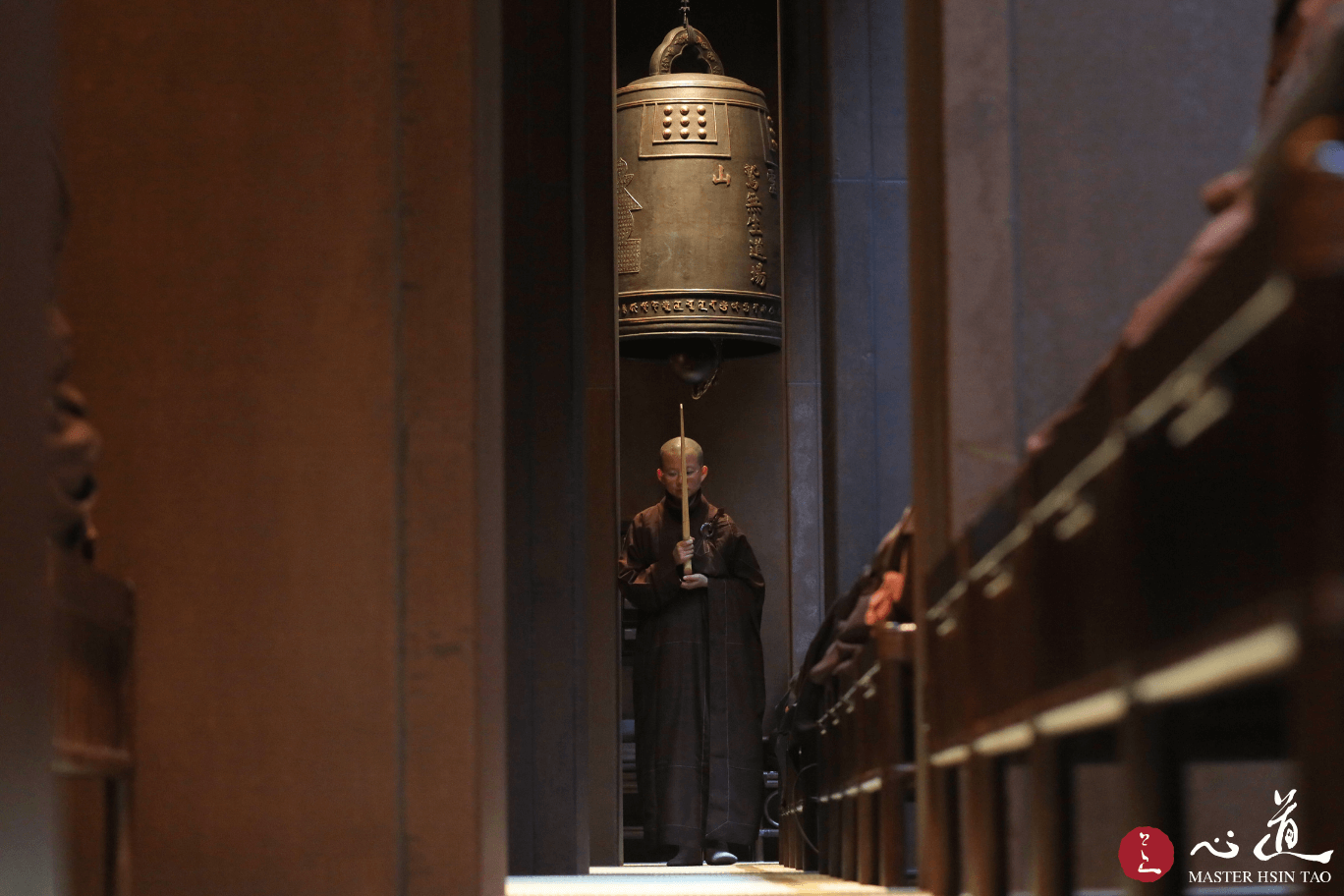

A practitioner should learn to be like the Buddha, maintaining a state of constant serenity and peacefulness. When interacting with sentient beings, one’s speech should be kind and harmonious, enabling them to joyfully receive the transformative influence of the Dharma. This is the practice of “harmonizing connections and taming the mind.” Taming the mind is itself a form of practice, and we attain a state of notionlessness, non-abidance, and non-conception. In this way, we remain unobstructed in daily life, and can give rise to mind free from attachment—this is Chan.

A mind free from abidance, conception, and notions is Chan; a mind that abides nowhere is called Chan. Chan frees us from afflictions, from obstructions, and from the cycles of arising and ceasing. If we remain bound by notions, by abidance, and by conceptions, then thoughts will continuously give rise to discrimination, attachment, and to grasping at notions—and thus, moment by moment, we generate karma and perpetuate samsara.

A mind free from abidance, conception, and notions is Chan; a mind that abides nowhere is called Chan. Chan frees us from afflictions, from obstructions, and from the cycles of arising and ceasing. If we remain bound by notions, by abidance, and by conceptions, then thoughts will continuously give rise to discrimination, attachment, and to grasping at notions—and thus, moment by moment, we generate karma and perpetuate samsara.

As long as the mind is free of conception, free of abiding, and free of appearances, liberation becomes attainable. This is what is meant by transforming thought, transforming consciousness into wisdom. When we encounter challenges or circumstances, we should refrain from grasping at notions or clinging to them. In this way, attachment does not arise; there will be no constant proliferation of judgments of right and wrong, good and bad. Instead, moment by moment, there is no conceptual proliferation, no abiding, and no grasping at notions. This is the “true mind.”

Therefore, work is itself practice; work is a form of offering; work is a mode of cultivation. Our daily life provides us with a field for sowing merit, a place to cultivate virtue. If we neglect to cultivate merit in our daily life, or neglect to engage in practice within daily life, a multitude of afflictions will arise.

Therefore, work is itself practice; work is a form of offering; work is a mode of cultivation. Our daily life provides us with a field for sowing merit, a place to cultivate virtue. If we neglect to cultivate merit in our daily life, or neglect to engage in practice within daily life, a multitude of afflictions will arise.

If the intentions and thoughts we generate are negative, the karmic result will be unpleasant rather than thoughts of awakening and benefit. Thus, we must properly maintain our own minds, engaging in the practice of achieving Buddhahood beyond notions; we must be vigilant over our thoughts so that, whether at work or in daily life, we transform consciousness into wisdom, transform it into the aspiration for bodhicitta, and transform it into the mind of awakening.