The Illusory World, Ultimately Unattainable

All phenomena in the world are illusory and characterized by impermanence. Yet, we often fail to recognize this truth. For example, in the throes of heartbreak, the suffering we experience seems substantial and does not feel illusory; similarly, when tempted by wealth, the desire to acquire it arises quite tangibly—again, it does not feel like an illusion. So why, then, do we say that “the world is illusory”? It is because everything is impermanent. Even if one comes to possess something, it is fleeting, just like our own lives, which are likewise transient.

All phenomena in the world are illusory and characterized by impermanence. Yet, we often fail to recognize this truth. For example, in the throes of heartbreak, the suffering we experience seems substantial and does not feel illusory; similarly, when tempted by wealth, the desire to acquire it arises quite tangibly—again, it does not feel like an illusion. So why, then, do we say that “the world is illusory”? It is because everything is impermanent. Even if one comes to possess something, it is fleeting, just like our own lives, which are likewise transient.

At times, we suddenly realize that we have aged. While the body remains healthy, we still perceive ourselves as young, without any palpable sense of aging. But once physical decline sets in, we begin to understand: “I’ve grown old.” The body no longer functions as it once did. Thus, everything we possess in the world, beauty, wealth, and life itself, is impermanent and transient.

This notion of transience refers merely to a span of time; once the time and conditions converge, change is bound to occur. Our thoughts, too, undergo this process. Thought is karmic memory and our lived experience. It becomes our conceptual framework, and everything we perceive and retains eventually turns into our mental constructs.

This notion of transience refers merely to a span of time; once the time and conditions converge, change is bound to occur. Our thoughts, too, undergo this process. Thought is karmic memory and our lived experience. It becomes our conceptual framework, and everything we perceive and retains eventually turns into our mental constructs.

When we speak of all things being impermanent, this impermanence arises from the constant fluctuation of our thoughts. Just as humans undergo birth, aging, illness, and death, our thoughts pass through the phases of arising, abiding, changing, and cessation. A thought arises, abides momentarily, then changes, and finally ceases. Therefore, everything in the world is impermanent: our thoughts are impermanent, our bodies are impermanent—all phenomena are impermanent. And because of this, we should not form deep emotional attachments to that which is by nature impermanent. Once an emotion arises, it becomes clinging; and clinging gives rise to karmic obscurations. These karmic obscurations are difficult to abandon, yet hard to hold on to, and thus they become the source of suffering. This is what is meant by the term “ultimately unattainable.”

Therefore, only when we ground our lives in the understanding of everything as unattainable can we find true happiness. If we have not established this view of non-attainment, then we should recite the name of Amitabha. With consistent practice, the view of non-attainment will gradually take root in our minds. We should also recite mantras and uphold them properly; over time, we will let go of our attachment to the ever-changing phenomena of the world.

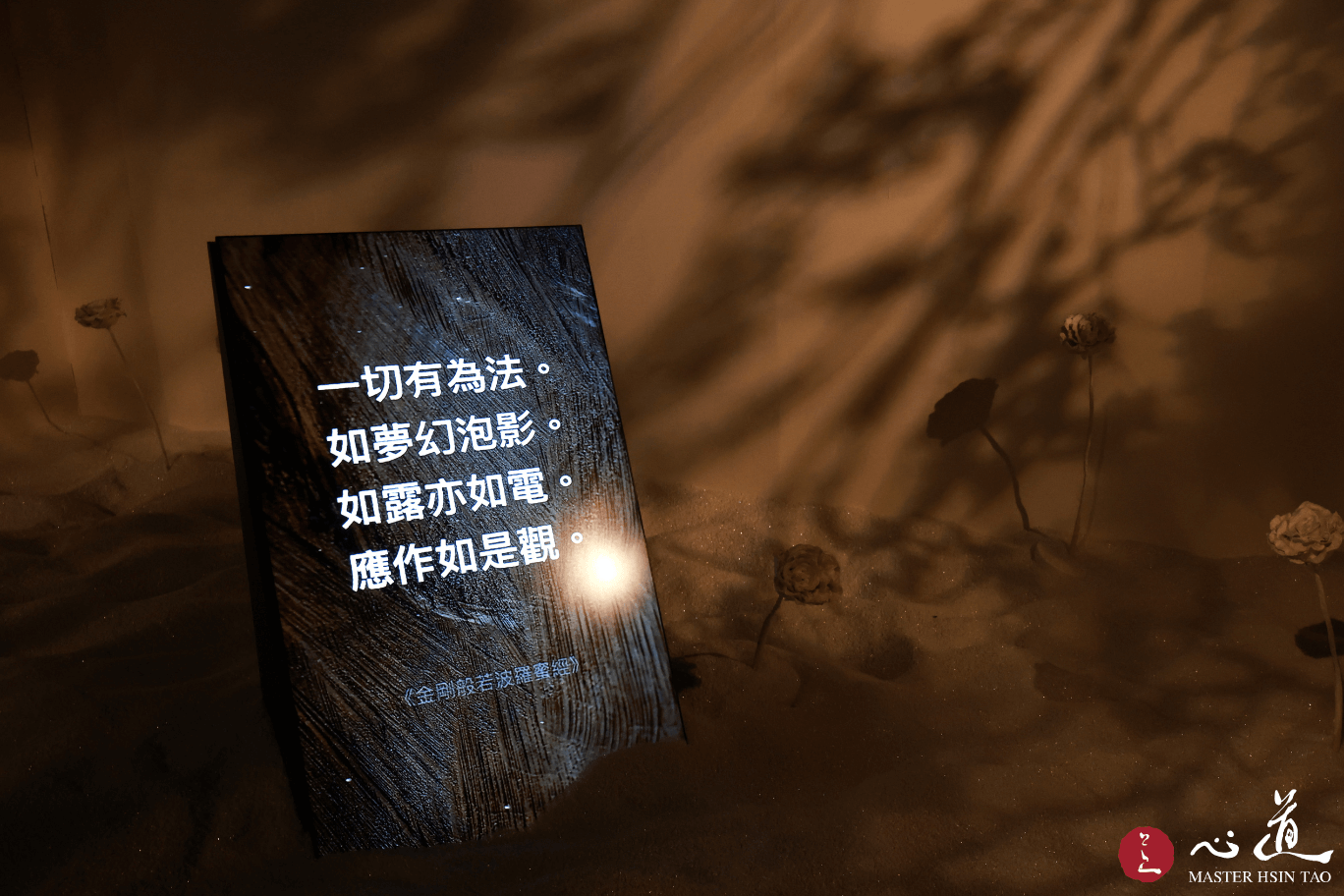

As the scripture says, “All conditioned dharmas are like a dream, an illusion, a bubble, a shadow. Like dew and lightning. Thus they should be perceived.” When we adopt such a view, we are less likely to fall into attachment and clinging, which in turn frees us from many forms of obscuration and mental affliction.

As the scripture says, “All conditioned dharmas are like a dream, an illusion, a bubble, a shadow. Like dew and lightning. Thus they should be perceived.” When we adopt such a view, we are less likely to fall into attachment and clinging, which in turn frees us from many forms of obscuration and mental affliction.